- Home

- Leslie Lutz

Fractured Tide Page 2

Fractured Tide Read online

Page 2

Marshall’s faint cloud of silt led me, like Hansel’s breadcrumbs, into the belly of the ship. And all the things that could happen to him spun through my mind.

He runs out of air, panics, dies. We fish his body out later.

Or maybe he runs out of air, finds a way out, and sprints to the surface, and panic makes him forget he shouldn’t hold his breath. The air expands in his lungs. They pop like balloons.

No, he remembers not to hold his breath, but he still ascends too fast. Nitrogen comes out of solution from his tissues. The bubbles that form lodge in his joints, his brain, every organ. He dies on the helicopter that comes to airlift him out, blood bubbling up from his lungs.

I forced the next two scenarios out of my head. Then, honestly, I panicked for a second. Worried I would run out of air too. Pictured myself in scenarios two or three, my corpse floating to the surface alongside Marshall’s.

My mask fogged and the world disappeared. I cleared it with seawater so I could read my gauge. The needle had dropped. A lot. I slowed my breathing. I couldn’t leave the ship without finding Marshall.

At the end of the hallway, I passed an opening. My hair, which had slipped out of its band, floated in front of my mask. Through the black veil, I swear I saw a flash in the corner of my eye. At first I thought it was Marshall’s yellow-striped leg, but no. It looked like a dive light. As I turned, the glimmer broke in two pinpoints, then disappeared.

Adrenaline made my hands shake. And now I was seeing things, from stress or the pressure or God knows what. Poor Marshall. Where on earth did he think he was going? He was going to get us both killed.

My light revealed two upended cots and a pile of jagged bits in the corner where a grouper floated, its eyes huge and unblinking, its mouth opening and closing as it watched me. I slipped inside the small berth, searching the other corners.

And then I felt it. A rush of something powerful in my blood. A flare of premonition.

I turned. Nothing. A corked glass bottle on its side. The hallway door yawning open, half off its hinges. My neoprene skin felt thinner. And I knew the next thing to swim near me would pierce me with a flip of a fin. The spines would impale me right through.

I kicked, turning in a circle while fire hosing my light around the room. Nothing. But my breathing, my heartbeat, my skin—they told me something different. I unclasped the dive knife strapped to my thigh.

My light moved smoothly up the walls toward the door. I stopped halfway, pointing the beam to the corner instead. The grouper had jammed its body within it, its eyes huge and shining in my light, the little fins moving slow. It wasn’t watching me. It was watching the doorway.

You’ll think I’m nuts, Dad, but instinct—the weird sense I knew what was going to happen—told me to shut off my light. I didn’t argue. Something was looking for me.

Click. The world contracted to the size of a sleeping bag, black so thick, a velvet cloth over my eyes. The chill dropped several degrees. The seconds passed. I breathed. In. Out. Rush of bubbles, heart pushing so hard, a caffeine-like rush. My body shook with the cold, as if my suit was nothing. I’ve never retained heat well, but this kind of chill went deeper, its tendrils reaching all the way into my lungs. I couldn’t see my gauge, but I could feel it, the needle slinking down. And as I was about to give up, to turn on my flashlight and get the hell out of there, suddenly the world wasn’t completely black anymore.

A faint glow, deep green. It grew in the hallway on the other side of the half-open door. As I watched it brighten, it felt familiar.

I swam to a corner of the berth, out of sight. The glow grew brighter. A voice inside me said Shut your eyes. You’re walking down death row. The worst of them wants you to look, so shut. Your. Eyes. And yes, the voice whispered, the thing out there, it really is that wicked. It really is that powerful.

I stilled. And then a current came, brushing over my face. A high-pitched scrape started up, long and slow, like something big moving through a tight space. A thrum as a piece of metal fell. The scrape softened, until it faded.

I opened my eyes. Blackness. My hands trembling, I flipped on my light. Gave myself ten breaths before I swam to the doorway to check the hall.

Nothing there. The dread gone, the fear eaten up by the need to find Marshall. I tried to slow my breathing and failed, looked at my gauge—800 PSI. Nine minutes left. If I could calm down.

A cloud of silt swirled in the hallway. I went deeper into the ship, where I thought Marshall had gone. I turned a corner at a T-junction.

Mid-sweep, my light moving into the deeps of the ship, something grabbed my arm.

I screamed a cloud of bubbles.

Dark brown hair caught in my light. A familiar mask, the neon-green stripe running down a black body.

Mom.

My relief lasted only long enough to see what she was dragging behind her.

It was Marshall, floating. His eyes were closed. His reg was in his mouth. But no bubbles.

Mom and I made eye contact. Pure panic. She tapped her oxygen gauge and pointed to the end of the hall.

Out. Now.

I grabbed Marshall’s other limp arm and pulled him from the beast. Somewhere close to the exit, I glanced at his face and my heart flipped into overdrive. You won’t believe me, but I saw it. His eyes. Something phosphorescent leaked from them, like tears.

I stopped swimming. Mom turned to me. In the crumbling hallway of a shipwreck, eighty feet down and running out of air, she actually took the time to give me the look. You’ve seen it a hundred times. The blame. Then, like a silvery fish slipping away, the look was gone, and she turned to the tear in the ship and swam through.

ENTRY 3

DEAD BODIES DON’T COOPERATE. They don’t grab hold of the ladder rung and pull themselves onto a dive platform. They don’t react when a four-foot wave knocks their faces against the boat engine. They don’t say thank you when you hold on to them tightly to keep it from happening again. You can’t know what it was like for me, struggling to keep him safe. A dead man. Safe. My brain kept trying to square the circle, like a mother arranging blankets around a dead baby.

By the time Mom, Phil, and I had dragged Marshall out of the ocean and onto the wooden platform, I was shaking from head to toe. I think I was crying, but with the salt water streaming from my hair into my eyes, I couldn’t really tell. A few divers who’d come up early rushed to the stern.

A tourist dropped her beach towel and kneeled next to him. “Oh my God. What happened?”

“Sia! Wake up and get his mask off,” Phil said to me.

I pulled it over his forehead, and Phil tipped Marshall’s head back to listen for breath sounds. Felt for a pulse. Started CPR.

The voices kept coming, tumbling over one another.

“Is he breathing?”

“We have to call someone.”

“This . . . This is terrible.”

“We have to get him to the hospital.”

“Is he—”

And that was it. I turned away, leaned over the side at the same spot Marshall had only an hour ago, and threw up. The waves crested and fell all the way to the distant blue horizon, and I felt sick in every bit of my body. Marshall had looked at me and nodded when I told him he would feel better if he listened to me. He believed me when I told him that if he just got in the water, everything would be okay.

By the time I’d finished chumming the waters, an uncomfortable silence had settled over the charter. Phil pulled the tank and BC off Marshall’s back and set them with the other gear. The rest of the divers came up one by one, and each time I got to hear the shocked questions all over again.

Marshall’s body lay under a blue tarp, close to the benches where we stored the extra tanks. Nothing but a shape under a dark plastic shroud. I sat nearby, my arms and legs numb, my hands like deadwood. If I had only kept my eye on him, none of this would’ve happened.

Mom put her hand on my shoulder. “You okay?”

I nodded and wi

ped my face with a beach towel. I was nowhere near fine.

She rubbed a palm over her wet hair and looked east, where the sun hovered three fingers above the horizon. The air thickened with the rising morning heat and the smell of neoprene.

Captain Phil walked by with a tank over his shoulder and gave her the once-over, which would’ve really pissed you off. How he could switch gears like that, I had no idea.

Mom’s wet suit lay in a heap at her feet, and she was wearing the white rash guard you gave her four years ago for Christmas, the one with the O’Neill logo in red and black splashed across the front. Mom has worn that and a pair of black bikini bottoms for every dive since you went away, like it’s now her uniform.

She sat down on a bench near me and patted the spot next to her. “Maybe this is a good time to talk about what really happened,” she said in Greek. The two guys within earshot at the cooler glanced over at us. People huddled in small groups, half-dressed in beach towels and bathing suits, talking in hushed, funeral home voices. The sound of crying drifted up the narrow stairs that went to the head. There really was no place to hide on a small charter. Mom’s fishhook gaze made that very clear.

“Everything was fine,” I said, my first language suddenly feeling rusty in my mouth. “Marshall was good, keeping his fins off deck. For a new guy, not bad.” I washed the taste of vomit out of my mouth and spit over the side.

“I don’t give a crap about how good his buoyancy was,” Mom said. “I want to know what happened.”

For the first time that day, I really looked at her. The lines of her face were hard. So were her eyes. I knew what she really meant: How could my daughter let this happen?

I dropped the gear onto the floor with a clatter. “He took off, Mom. I don’t know why.”

“Why weren’t you watching him?”

I tossed my hands up. “There was an octopus. He was adorable. Colette and I were checking it out. Marshall was behind us. And then he was gone. He swam off by himself, I guess.”

“You guess?”

“Okay, he swam off by himself!”

She looked baffled. “And why would he do that? No one with even beginner’s training does that.”

“People do stupid things. You know that.” My voice was rising, but I didn’t care. No one could understand us anyway.

“You sure you didn’t leave him behind, Tasia? I’ve seen you do this kind of thing before.”

“I’ve never left a diver.”

“No, but you push the edge of the decompression limits. Penetrate a wreck without knowing where all the exits are.”

“I know what I’m doing.”

“And what about that shark last week, handfeeding him? That was—”

“The nurse shark? C’mon. They’re like puppies.”

“Do you want to keep your fingers? I swear to God, just like your—” She stopped and rubbed her face. Calming herself down.

“Like your father? Is that what you were going to say? I think I’ll take that as a compliment.”

“He wasn’t perfect, you know,” she continued in a deliberately calm voice. “Once you get underwater, you take risks. That’s all I’m saying. He was the same way.”

“Was? He’s still alive, Mom. When did you stop talking about him in the present tense?”

She pointed at Marshall and cut me off. “Look at what happened!”

As her words rung out, the chatter on the roof deck died. She took a breath and stood, apparently done with our conversation. Grabbed a stray mask and threw it in the nearest barrel of fresh water, sending a cold, wet slap against my shins. Her motions were stiff, unnatural, as if she’d forgotten how to tidy up after a dive. I watched her gather gear. Avoid my eyes. And Dad, you don’t know how I felt. She couldn’t even look at her own daughter.

The boat rocked her off-center as she grabbed a wet suit and switched on the shower, rinsing it down. Some of the water ran across the floor and pooled underneath Mr. Marshall.

“I didn’t leave him behind,” I said.

“How did he get lost, then? Explain how.”

“It was textbook. Everything I did. Until he left us.”

She put her hands on her hips, examining my expression. Finally, she exhaled and shook her head. “I shouldn’t have let him come with us. Too green. Not enough bottom time.”

“Gee, thanks for trusting that I’m not lying to you.”

She ignored me and looked west, toward shore. “We’re heading to the marina. The cops are too lazy to come out here, so they’ll meet us on the dock.”

A wave of relief washed over me. I knew I wouldn’t get an apology from her—that part of her personality has been broken since you went away—but all I wanted was to start our motor and get as far away as possible from the USS Andrews.

“Matt’s pretty close,” she continued, focused on the western horizon again. Her eyes said she couldn’t get there fast enough. I followed her gaze. Nothing in the distance but whitecaps and a few seagulls.

“His charter will be here in forty-five,” she said. “Maybe an hour. We’ll transfer the rest of the divers to him.”

“Isn’t Felix with him today?”

She nodded.

I looked away and took a sip of water. “I don’t want my little brother to see a dead dude.”

“He won’t.”

“He’ll hear about it.”

“Yeah . . .” She rubbed the back of her neck with one hand, distracted. “He’s seven. He understands death. He can handle it.”

“I’m seventeen and I can barely handle it. Call someone else.”

The wind was dying, but it still had the strength to carry a mist of sea spray, and I breathed in the sharp tang of salt. That’s when the feeling hit me again, so strong I was sure everyone within ten feet of me could feel it too.

Too cold, too dark, too deep. Leave now.

“We should all go in together,” I said. “The cops—won’t they want to talk to the others?”

“No, they’ll just want to talk to me. And Phil.”

That didn’t sound right, but everything I knew about police procedure I’d learned from reruns of Law and Order. And your trial, of course. “Captain Matt can’t be the only guy out here. It’s a Saturday. And it’s gorgeous outside.”

She shrugged. “His is the closest scuba charter. It has a group headed to the Haystacks, mostly snorkelers, but it’ll do.” She paused, clearly working the details out in her head. “You can help our people get one more dive in and then head back to shore.”

“The cops will absolutely want to talk to me. And you really think anyone’s going to even think about going in the water after what happened to Mr. Marshall?”

Mom moved to a bench under the sunshade and sat, leaning her elbows on her knees and clasping her hands together. She sat there for a moment staring at her hands, gathering her thoughts. I wasn’t sure what about my question had her so stumped. It seemed simple enough to me. Everyone would want to go home.

“Tasia, do you remember what happened on the Spiegel Grove?”

I’d heard that story from you about a hundred times. But Mom kept going, like she does, not waiting for me to answer.

“Four divers went into the ship, and only one came out,” she said.

“Yeah, Dad said the Spiegel eats divers.”

Most kids get campfire stories about hitchhikers with hooks for hands—but you, your scary stories were never far from the ocean.

“How long do you think it took before people were diving in the Spiegel Grove again?” Mom asked.

I took a sip of water and thought. When our apartment manager lost her sister, she wore black armbands for a year. A friend of mine didn’t celebrate her January birthday because her brother had died in August. “I don’t know, three months?”

“A charter was out there the next day.” Her gaze went to the tarp under the sunshade. Most of the other divers were on the roof deck whispering in huddles, too freaked out to be any closer to a dead bod

y. A few stood by the cooler, fishing through the ice for bottled water.

“Life just goes on, Tasia. After everything hits bottom, it just goes on.”

She looked away, but the pain I’d seen in her eyes told me we weren’t talking about Mr. Marshall anymore. And as I stood there on the boat, two feet away from the biggest mistake I’d ever made, I knew where I was going the minute I got to shore. To see you. If anyone could understand what I was feeling after killing another human being, it would be you. No offense.

The dark feeling that hit me when we first arrived at this spot in the ocean welled up again. I looked at the white buoy and the line leading down to the USS Andrews. “We should go now, Mom. Just leave. Together.”

And I told her. I did, Dad. I tried to stop everything before it could start. I told her about the weird phosphorescent glow I saw in the ship’s hallway, and the strange feeling. But somewhere in the middle of my explanation, her lips started to curve up into a smile.

“You had me worried there for a minute.”

“What?”

She put her hands on my shoulders. “You were narced, honey.”

“I wasn’t. Nitrogen narcosis makes you feel drunk. My head was clear.”

“You were narced.”

“I was thinking straight.”

“You went off by yourself to find him. Risk-taking—that’s part of it.”

Phil, who was fiddling with a regulator hose, chuckled. “First rapture of the deep. You’re a real diver now, girlie.”

Mom glared at him, and I hated Captain Dirtbag a little more than usual. “Stop calling me that,” I said.

“That’s what seventeen-year-old girls get called on my boat.”

“What are you gonna call me when I turn eighteen?”

Phil gave me an oily smile. “Fair game.”

I opened my mouth to tell him off, but Mom got there first, her face flushing. Phil waved her off and walked away like she couldn’t take a joke, but all I could think about was the rapture of the deep. Phil and Mom together, it was enough for me to doubt myself and what I thought I saw. But I couldn’t shake the feeling something was wrong below our charter.

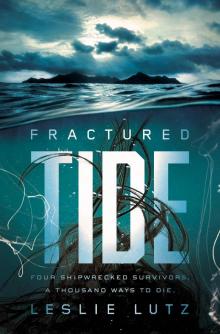

Fractured Tide

Fractured Tide